Society > Housing

Housing

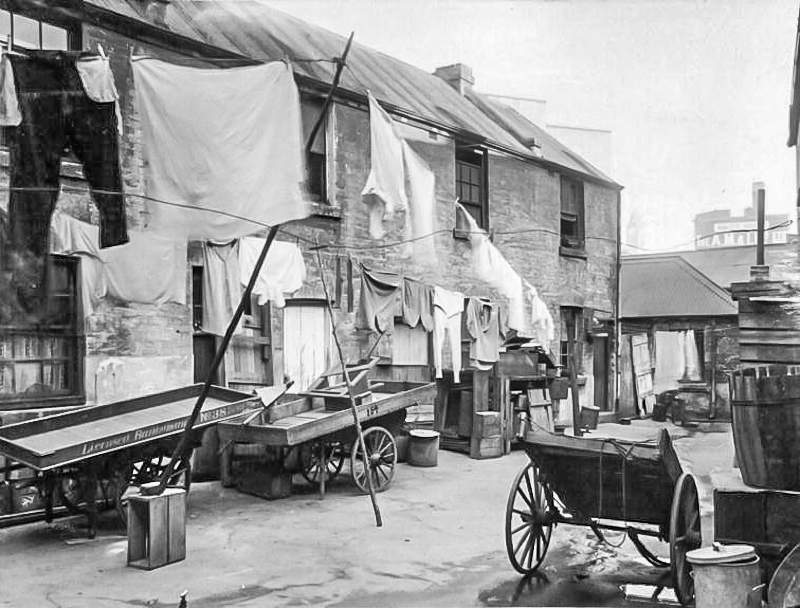

Among palatial wool stores and a few mansions, most housing was cheap and unhealthy. This was demonstrated in the 1870s, during the 1900 bubonic plague and in Mayor John Harris’s well-publicised tours. Advocates of ‘slum clearance’ (John Harris and Allen Taylor) had a strong case – but could not say where evicted families should go, or how people could get to their work.

A rare exception to miserable housing was Ways Terrace apartments, built by the City of Sydney in 1925, and designed imaginatively for working people. All others rented cottages from landlords who had no incentive to maintain their properties. As industries expanded after 1890, the number as well as the quality of housing declined.

The expansion of car ownership from the 1950s led directly to freeways and carparks replacing cottages and facilities. Residents campaigned for social housing, and the Department of Housing did build some flats. However, governments were beginning to think in new terms. Post-industrial Pyrmont could provide homes for the City’s professionals and office-workers. As part of the Urban Redevelopment project, City West Development Corporation (CWDC)’s mission was to sell government land and stimulate private sector development.

This trend was resisted by long-term tenants, many of whom had lived here for generations. The outcome was predictable, but these battles energised resident action groups, allied to the heritage movement. In the process the previously dominant Labor Party branch crumbled and was displaced by independents such as Michael Matthews who better represented the needs of residents. The trend was also resisted by squatters camped in abandoned cottages. Nevertheless, ‘urban renewal’ meant high-rise apartments and the end of a working class suburb.

An important exception to this general tendency was City West Housing, a branch of CWDC, which developed a range of rental apartments that were both affordable and well maintained.

Seal’s Place, 1923