Society > Pyrmont Society

Pyrmont Society

As Pyrmont society formed in the late nineteenth century, it was based on three pillars. Trade unions formed very early, and enjoyed massive support among working men. Churches were built and filled with loyal congregations, who provided material and moral support as well as spiritual guidance. And the Labor Party was unchallenged for decades. These pillars crumbled only in the late twentieth century when heavy industry wound down, the population dwindled, and congregations shrank. The New Pyrmont Society is forming on very different bases.

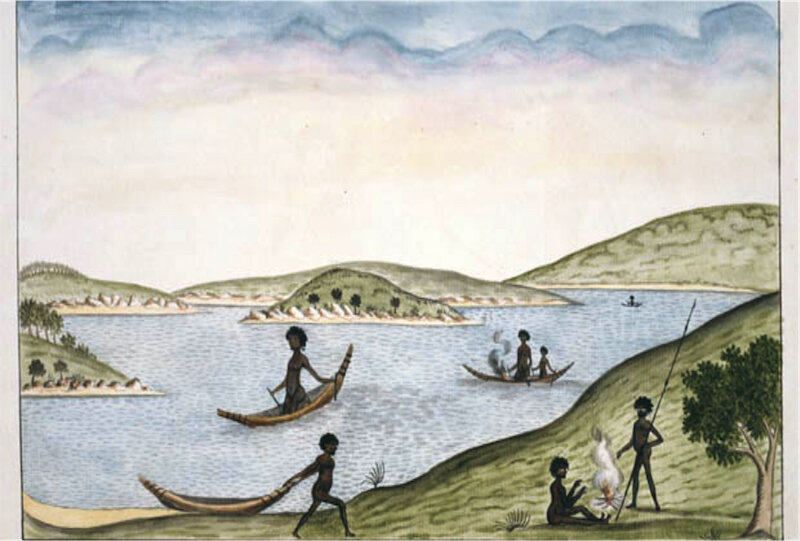

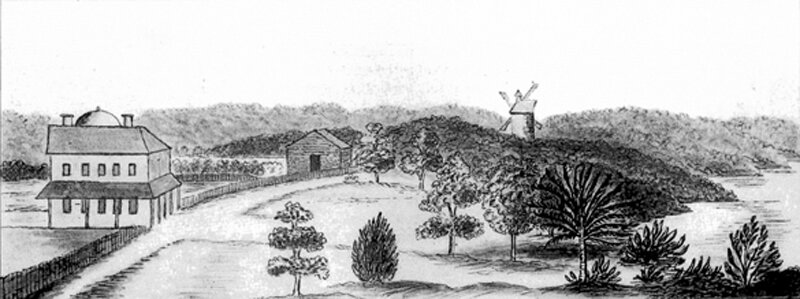

Pyrmont had no council to negotiate with the State, the City, or the giant companies that built businesses here. Society evolved largely in response to forces outside the peninsula. For the first decades of the nineteenth century, ‘society’ comprised two great landowners, their employees and retainers, and Gommeriagal who camped, fished and hunted without much interruption. The maritime industries on the shoreline did not employ large numbers, even after Pyrmont Bridge opened.

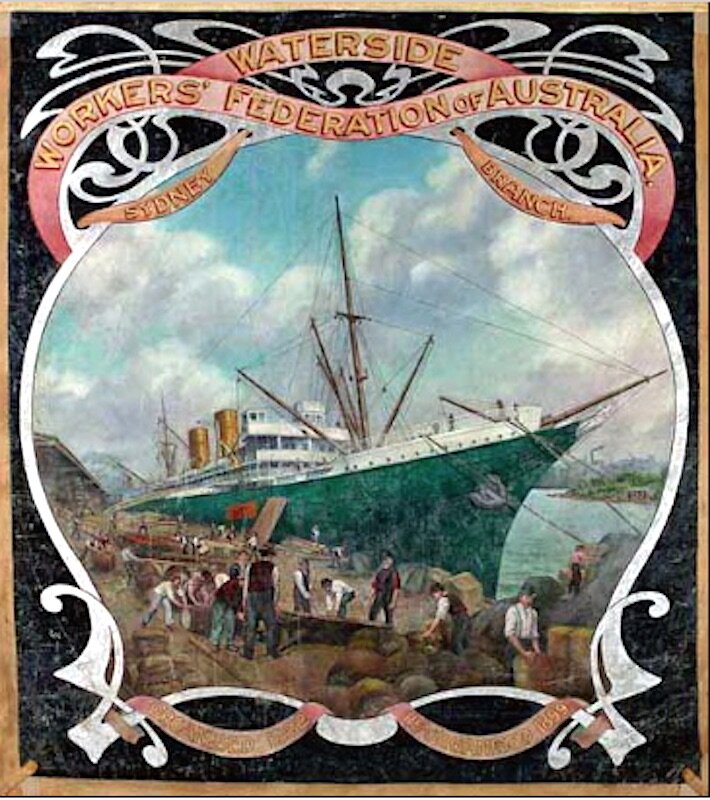

When the population did increase, especially from the 1870s, most residents were managers of the quarries and companies, or their employees. It is not surprising that trade unions (of stonemasons and waterside workers) were among the earliest forms of social solidarity. Union membership and sometimes militancy were the hallmarks of Pyrmont society for nearly a century. Labor Party leaders and union officials banked on unionists’ support, but working men were often inconveniently militant, as in the 1890 Maritime Strike and the General Strike of 1917.

Pyrmont was a decidedly macho society. Working men would resist authority in several domains: from the 1890s to the 1940s, waterside union members fought pitched battles against unemployed non-unionists (scabs or snipers) for jobs on the docks. They insisted on their right to bet their wages on two-up or prize fights. And wharfies compensated for dreadful working conditions and low wages, by appropriating goods that often fell off the back of trucks. Among laws that offended working men were liquor laws, justifying extensive sly grog consumption – including, by some accounts, the police themselves.

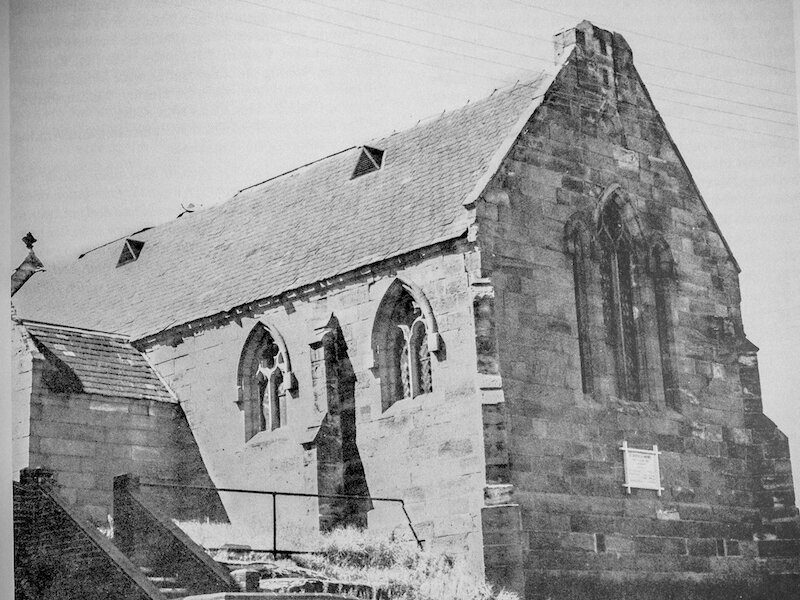

The men’s sisters, wives and daughters saw matters in a different light, and often found social, moral and material support in the churches. Almost all families attended church services, and (mainly women) members of the congregations organised most of Pyrmont’s social events – dances, tea parties, concerts and picnics. Most children attended church schools as well as Sunday school. Four congregations flourished in the 1900s: church membership continued to be important, especially for women, even as a shrinking population could support only one – and St Bede’s, the great survivor, was threatened with closure. Closely related to people’s attachment to churches was the great extent of charity work. All churches organised support for their members, and for others who fell on hard times. In the same spirit, trade unions supported unemployed members – and extended their support to seamen and other visitors who fell foul of their employers.

Then there was the Labor Party. Party leaders fought ferocious factional and ideological brawls at State and Federal forums, but they dared not forget the practical needs of their loyal constituents. During the 1930s, for example, Labor was outflanked by the Communist Party, which came to the aid of tenants evicted as industry expanded. At the level of the Pyrmont branch, the Labor Party became in effect an employment agency. Pyrmont did not elect a non-Labor member for eighty years. In exchange, the party organised the first paid jobs for their sons, usually as City Council employees.

Pyrmont Society organised itself successfully around unions, churches and ALP until Pyrmont itself faded away. Heavy industry closed, shedding a large work force. As the population shrank, so did the churches. Fewer people meant fewer voters and less political patronage. In the 1990s, the State government began to plan a new Pyrmont of hi-tech companies, high-rise apartments, and a majority of well-to-do residents. The old Pyrmont Society was no more, and the new Society will organise itself on new foundations.