Society > Charity

Charity

Poverty was endemic, prompting people and institutions to organise relief. Circumstances differed, and so did methods and motives. Workers’ mutual support organisations in the early 19th century evolved into trade unions, tackling poverty by increasing wages. Industrial action sometimes succeeded, and usually hurt workers’ families. During the Great Australian Strike of 1917, The Sun (4 October 1917) admired the way the poor helped the poor, but lamented the conditions of wives and children:

In the little lanes and by-streets around Pyrmont the poverty is appalling. … On either side the streets are overlapping dens and dungeons, and the mothers behind the brick walls never cry except in the silence. Year in and year out they exist in their poverty, for the slums… were always there, and the strike has but intensified the distress. And each hovel, even though it presents a clean window curtain to the world, is the centre of a little tragedy.

During the depressed 1930s, the Pyrmont Food and Relief Fund told the Labor Daily (2 May 1933):

We opened our work on May 14, 1928, in the middle of a terrible waterside strike, when many children, we found, often went hungry. At the opening we served over 250 free meals dally. A few weeks later we opened for homeless men, and the following year we opened our first shelter for 60 men. In May, 1931, we made provision to house over 200 men nightly.

The children are still served with a hot mid-day meal, and to the men over 600 meals are issued daily. We also issue through the courtesy of certain butchers a large quantity of soup bones and meat, and groceries are issued according to the allowance of funds, and gifts of food.

Cast-off clothes and furnishings are also given in cases where we have found families sleeping on the floor with very little covering.

Such organisations were supported by the trade unions. Other kinds of aid were organised by more affluent elements. The Boys’ Brigade, for example, built a spacious centre for the poorest boys in Pyrmont and other inner-city precincts. It was opened in 1925 by the Governor General, and its Christmas and other celebrations were patronised by Rotary, and the Knox, Fairfax and similar leading families. It flourished until the 1970s when it was bulldozed to make room for a highway.

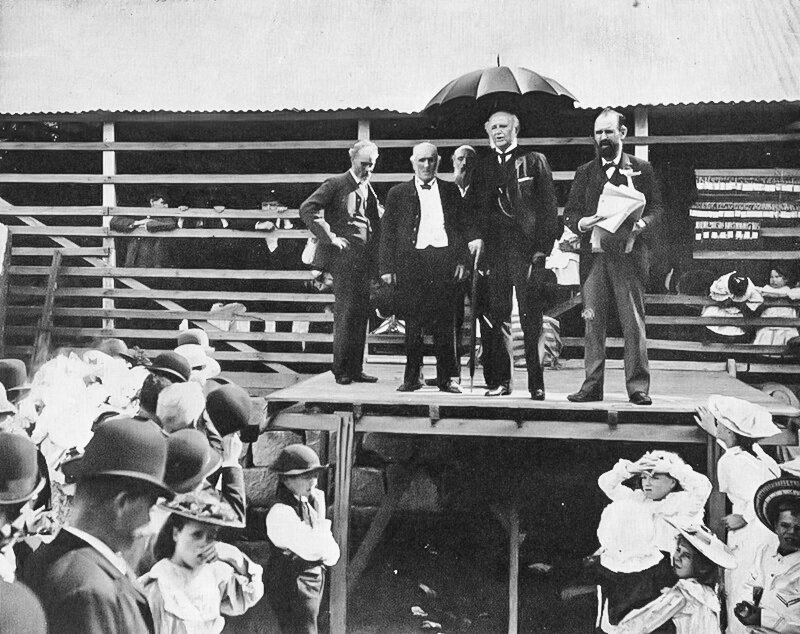

Pyrmont companies also did their bit. CSR’s picnic in 1886 initiated a tradition of entertainment for the families of employees – and in the 1930s CSR’s Clydesdale horses paraded up and down Harris Street on festival occasions, while their drivers threw sweets to the children. Festival Records – an unfailing attraction for local youngsters - had a big Christmas party in St Bede’s hall one year, starring the singer Johnny O’Keefe.

These ventures pale in significance beside the work that the churches did, all the time. They raised and distributed funds, food and clothes, and inspired others to do the same. Mr and Mrs McDonald ran a soup kitchen, gave clothes away and handed out oranges to the kids. The Uniting Church ran a popular and useful laundrette, whose manager would also pass around clothes and other things.

In Pyrmont, poverty was a fact of life – and so was charity. As Irene Madlin put it, charity “was their culture”.